United States Annual Budget, Part II

The federal government spent about 6.4 trillion dollars ($6.4 T) in Fiscal Year 2022 (October 2021 to September 2022). That’s about a quarter of the United States’ 25 trillion-dollar GDP, or about $20,000 per person for the 330 million inhabitants of the United States, or $25,000 per person for the 257 million adult inhabitants. What does it do with all that money? Let’s take a look at the FY 2022 numbers.

Composition of the Budget

Each box in the figure represents spending on a different governmental function. The total spending for each row of boxes is given by the height of the row, such as $1.4 T for Health. The fraction of that spending going to each function is given by the width of the box, such as about .35 of Health spending going to Medicaid.

About half a trillion dollars went to paying interest on the ever-expanding debt. That is money that needs to be paid based on debt from past spending. The other six trillion went to actual goods (things the government bought), services (things the government paid people to do), and transfers (money the government gave to people) that were spent in 2022.

Often the budget is discussed in terms of discretionary spending, the amount of which is set by Congress each year, and mandatory spending, which is set by rules already codified in past laws. Much of the mandatory spending is in entitlements. This word has taken on a negative tone because often people are described as “entitled,” when they feel they are entitled to things, such as admiration or wealth, that they really are not. The actual meaning of the word is simply “having a right to certain benefits or privileges”. For example, everyone sixty-five years or older is entitled to payment for medical treatments through Medicare.

About half of the six trillion in new spending went to mandatory medical spending (Medicare and Medicaid) and income for old people and disabled people (Social Security and various funds for retired federal workers and veterans). The bulk of this spending – Social Security and Medicare – are enormously popular because everyone who lives long enough benefits from them. Medicaid is only for people with low incomes, but a big chunk of it goes to people who live in nursing homes, many of whom were not low income until the high cost of nursing drained their savings.

Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid are often separated from the rest of the federal budget because they are paid for differently – mostly from payroll taxes rather than the income tax. Here I am just looking at spending rather than taxes.

The Income Security row of mandatory spending, about $0.8 T, is a big part of what many people think of as the welfare state, meaning government support, such as food or income, designed primarily for people with low income. This also includes unemployment insurance, which (like Medicaid nursing home support) is a benefit which a broader cross section of society uses at some point. Tax Credits include things like the Earned Income Tax Credits for “low- to moderate-income workers and families” but also the Child Tax Credit which is distributed more widely to families with children.

The final rows of the mandatory spending group are primarily some recent programs. One is the student loan forgiveness program recently announced by the Biden Administration. Though this item is listed as costing $0.4 T, it is currently held up in court and I am unclear on whether it actually spent all of this money in FY 2022. It may never be allowed to be spent, depending on how the court decisions go. Even if it is allowed to go forward, I believe the program is designed to not spend as much in subsequent years. Similarly, the Other Mandatory row includes spending programs related to buffering the economy from the Coronavirus shut-downs and their aftermath, and is expected to wind down.

All the discretionary spending – money allocated by Congress each year – amounts to only $1.6 T of the total $6 T of spending. A big chunk of this, around $.7 T, is for Defense, a euphemism for US military spending. Whether that military is purely for defense is a matter of opinion.

If you take away mandatory spending and the military, everything else the federal government does costs about $ .9 T, including a bit more than $.2 T for health and other science and technology, $.1 T for transportation (including big ticket items like highways) and $.07 T for international affairs (a perpetual favorite for spending people want to cut to balance the budget).

The Budget Over Time

A much-discussed feature of the US budget is the growth of entitlements due to the Baby Boomers reaching retirement age and rapidly rising medical costs. This trend was actually not as pronounced as I expected.

Over the long term, Medicare and Medicaid has had continuous growth since their inception in in 1965. Since 2009, Medicare spending has gone from a bit less than 3% of GDP to a bit more (with a Covid spike in 2020); it had larger growth in previous years. Medicaid actually had larger growth of almost half a percent of GDP since 2009. Social Security mostly hovered between 4% and over 4.5% for the 32 years before 2009, took a big step upward from 2008 to 2009 because of the Great Recession, and has slowly risen from over 4.5% to about 5% since then.

Meanwhile, military spending is way lower than it used to be, down from 7%+ numbers in the 1960s, and smaller peaks during the Reagan administration and the Iraq and Afghanistan wars to about 3% of GDP. This is about as small as it’s ever been since before World War II.

Though The Big Four of Social Security, Defense, Medicare and Medicaid are some of the largest items in the budget, “Everything Else” (all other expenditures besides interest payments on the debt) is not negligible: since about 2000 it’s had a floor of about 6% of GDP, with large spikes due to Covid and the Great Recession. Still, taking away The Big Four is a large majority of budget. The small trends in The Big Four since 2009 are dwarfed by the Covid and Great Recession spikes.

Data Sources & Peeves

Detailed 2022 budget data comes from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), The Federal Budget in Fiscal Year 2022: An Infographic. This shows budget numbers with circular graphs that look cool but which I think make it harder to compare different quantities. They are probably less space-efficient than rectangular graphs, which is important because the budget information needs a fair amount of text and it is hard to include all the categories while still making all the text legible. CBO solves the problem by moving detailed information to additional pages and displaying it with a different kind of cool but space-intensive chart. There’s a lot to recommend their graphics approach but I think the presentation here is somewhat more compact.

There is a slight discrepancy between CBO numbers and here because CBO subtracts a few hundred billion dollars that the government collects in fees. It seems to me that goes in a different category than spending, since the numbers don’t consider other government receipts such as taxes.

Time history of spending comes from White House Historical Tables except for Medicaid, which comes from CMS National Health Expenditures (NHE).

I’m an amateur who has been examining federal budgets since the mid 1990s, when the new Republican majority in the House of Representatives was raising an alarm about “out of control government spending.” I grouped different budget categories as best as I could, guided by the CBO website.

This is information that should be readily available to all Americans, but interpreting the exact meaning of the budget categories in the CBO infographic was not always easy. I miss the old Statistical Abstract of the United States, published every year by the Census bureau until it was discontinued as obsolete around 2011. It remains far too difficult to get up-to-date budget data. My searches found many detailed discussions in CBO and elsewhere of particular budget issues, and general descriptions (mostly from several years ago) from various foundations and media sources. However, in the age of hypertext there should be a comprehensive description that let’s readers find a simple, top-level description with snapshots and time series but with links to drill down into finer details and legal definitions.

Budgets are stereotyped as dry and uninformative, but they represent a portrait of everything the government is doing. At a time when the debt series show-down has people attacking or defending the budget, it is important to know what the budget actually is.

Plots were made in Matlab, mscripts plotfedcats.m and plotfedparts.m.

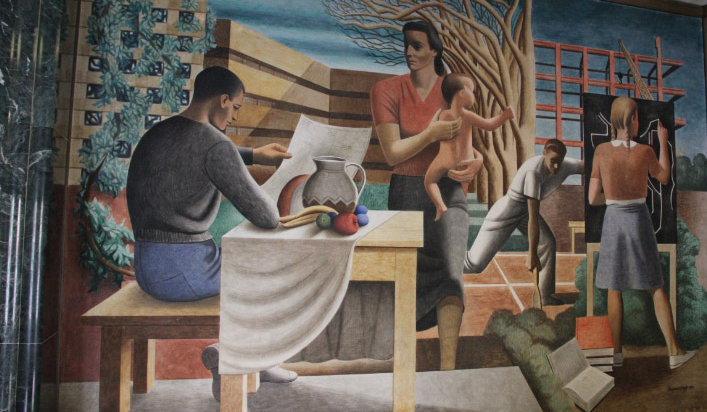

Cover image is [most of] “Security of the People” by Seymour Fogel, mural in Wilbur Cohen Building, Washington DC.